Stand for Something and Mean it

This article first appeared in the 2019 Field Days edition of the New Zealand Farmer’s Weekly.

The first video rental store opened in 1977. For a $50 annual membership, customers could rent movies for $10 a day, taking them home to play on their $6,000 VCR.

Twenty years later, along came $1 rentals and the DVD player, a relative steal at $1,500.

Today, $12 a month and a $100 smartphone gets you all the movies you want.

Welcome to the world of the zero marginal cost business model.

Coined by economist Jeremy Rifkin, zero marginal cost is a useful way to understand the trajectory of technology and price. Stepping back to high school economics, we recall that marginal cost is the additional cost incurred to add a unit of production. On the farm, that means shouldering extra acreage, manhours, vet bills and transport costs for every additional stock unit.

Businesses like Netflix, Spotify and online education are zero or low marginal cost information products. Once the infrastructure is in place, it costs next to nothing to scale up and add customers. Uber, Tesla and Amazon demonstrate the disruptive potential of low marginal cost models in the physical world.

Food is next.

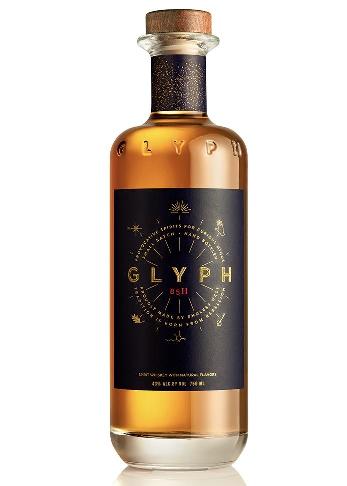

Our future food competitors will be low marginal cost alternatives – plant-based or cultured meat and milk, vertical horticulture or molecular whiskey and wine. For these producers, scaling up is relatively cheap. The real grunt of their business model is in their IP. Once the “recipe” is right, the marginal cost of making more is minimal. The end result is a cheaper product, that’s constantly improving, with the potential to steamroll higher marginal cost competitors out of the market.

Glyph - a molecular whiskey - is indistinguishable from it’s 24-year aged traditional counterpart. It retails for around $40 USD a bottle.

There is no place for NZ agriculture in the zero-marginal cost game.

Innately, we know that ours is a different path – one of provenance, premium and deep customer connection. It’s a great strategy. It plays to our strengths, our heritage and our sense of Kaitiakitanga (guardianship). And it’s what our customers want.

Emerging in parallel with the zero-marginal cost model is the experience economy. I like to think of it as fast, cheap and functional vs slow, expensive and meaningful. Those global citizens who can afford to are looking for products that shape their identity, define their social status and make life worth living. To stay competitive, the food and fibre we produce has to make our customers slow down and feel something beyond taste and personal pleasure.

That’s easier said than done. There is no blueprint to transition a national industry from a technical, productivity focus to a strategy based on intangible values like authenticity and customer connection.

As it stands, we have a foot in both the marginal cost and experience economies. Our apprehension to take a leap of faith into the experience economy is entirely reasonable. Generations of investment – in infrastructure, human capital and personal identity – are sunk costs in a model that up until now was rational, profitable and something we were exceptionally good at. Change is hard.

But what got us here, won’t get us there. To earn a niche in the experience economy, we have to choose to be remarkable.

What do remarkable brands look like? Their actions and principles speak louder than their advertising. Patagonia made headlines when they endorsed two US senators with strong conservation platforms. Tesla doesn’t run ads, but firing Elon Musks’ personal car into space on a SpaceX rocket spoke volumes. Rolls Royce has never advertised. Even Nike waded into divisive social justice issues last year, igniting praise and backlash by running a campaign with a controversial NFL player.

The front page of the Patagonia website in December 2017. How many brands are confident enough in what they stand for to take on a President?

To compete in the experience economy, we need to stand for something and mean it.

Top producers like First Light Foods are leading the way. Their success is what happens when we combine exceptional farming with authentic action and storytelling.

Our great experience economy opportunity, our moonshot, is for all NZ food and fibre to be like First Light. But we have to build it before our customers will buy it. That requires remarkable actions that broadcast our values, beyond traits like pasture fed and hormone free. Banning feedlots, rejecting imported feed, refusing to live export our animals, ending bobby calf wastage, committing to on-farm biodiversity, measuring carbon capture, mainstreaming regenerative farming, pioneering calf & cow milking, sourcing ethically-produced fertiliser and transparent supply chains. We need to prioritise R&D that promotes and protects our reputation, even at the expense of productivity.

These are all difficult and expensive actions, but that’s what makes them powerful. When we make a values-based connection to our customer, price premiums and new revenue streams become possible. Why not a Kiwi meat, milk & produce box for a taste of southern summer in the middle of the northern winter? Or international Kiwi country-life roadshows where we teach regenerative living and share seeds, native food and Māori values. How about a global Patreon (online donations) campaign to back Kiwi farmers pioneering a better food system? At home, urban Kiwis will support our farmers transition to this new model with local price premiums or temporary government subsidies.

We don’t have to launch rockets or court controversy, that’s not our way. A quiet, humble but unwavering commitment to our land, animals and people will be enough for a world, desperate for authenticity, to take notice. Let’s show them what we stand for.